About this site

My website has been online since 2013. It serves as a personal wiki where I collect bookmarks, excerpts, and thoughts. Some pages are rougher and mostly useful to me, while others are more polished and intended for other readers. Cam Pegg’s defunct “Notes to Self” listed the site as a “digital garden”.

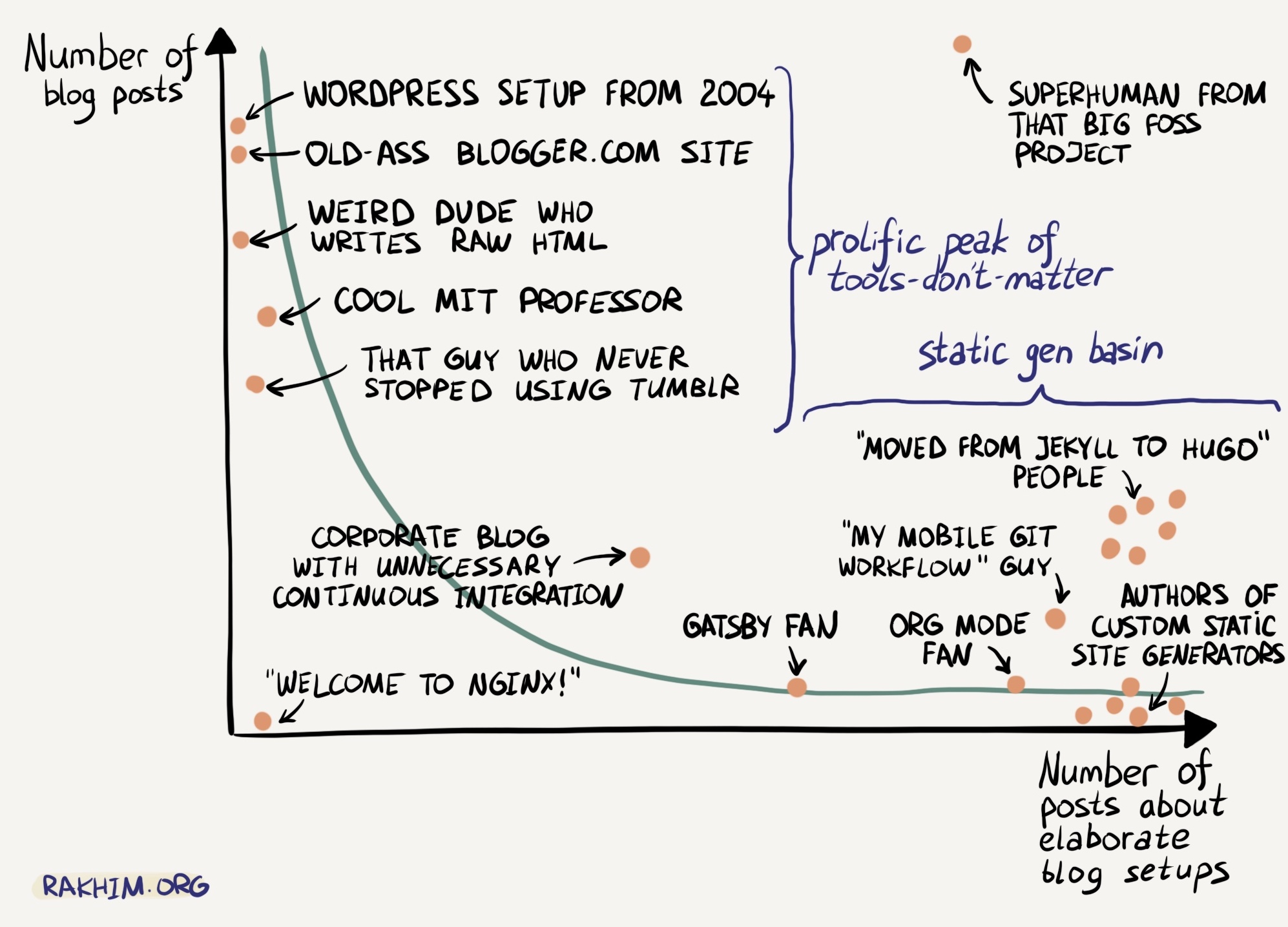

In its current incarnation, the site is a collection of interlinked HTML files produced by a custom static site generator and served by Caddy. The result is a wiki that only one person can edit.

Influences on the site include Wikipedia, the Tcler’s Wiki, Ward Cunningham’s wiki, the Memex and Ted Nelson’s writings, TiddlyWiki, TV Tropes, Everything2, and Everything Shii Knows.

The common theme of these sites is writing evolving pages instead of finished blog posts. Other themes include internal linking, organizing link collections into documents (similar to Memex “trails”), and one page per subject.

The biggest influence is Gwern.net. Watching its development was what made me turn a stalled blog into a personal wiki. Besides the philosophy of perpetual drafts and writing for your future self, the influence also shows in the design. I have borrowed many design elements from Gwern.net that are not visible to the reader, such as Pandoc, link archival, and the interwiki link syntax ([favicon](!W) to link to “Favicon” on Wikipedia), as well as visible design elements such as the subscript dates and link icons.

I experimented with long URLs derived from the page title by a simple algorithm. What I learned was that URLs should be short. They should also use a minimal set of characters in the path ([/A-Za-z0-9.-_]) and avoid query strings.

In the Fossil incarnation of the site, I decided at first to embrace Wikipedia-style page naming: my page URLs would include the full title. I thought it was neat: one less thing to worry about, less friction when creating pages.

My Fossil URLs started out as

https://dbohdan.com/wiki?name=How+

Internet+ communities+ function

and evolved to

and then

First, I realized the query part of a URL is too easily lost. Looking for alternatives, I discovered Fossil allowed /wiki/Baz+foo instead of /wiki?name=Baz+foo. I didn’t link to my site from many places, yet I still noticed that spaces encoded as + in the path part of the URL were sometimes a problem for linking and automatic URL detection. Encoding spaces as %20 worked more often but looked even uglier. Eventually, I gave up on the idea of page names with the full title.

When I migrated off Fossil, I dropped the /wiki/ part. My current URL format uses one or more lowercase English words joined with dashes:

- Sam Hughes, “On short URLs”, https://qntm.org/urls2011

- Derek Sivers, “Short URLs: why and how”, https://sive.rs/su2022

- Gwern Branwen, “Design Graveyard: Long URLs”, https://gwern.net/design-graveyard#long-urls2023

- Clean URL

I cannot fully endorse Derek Sivers’s approach. I think regular words are preferable to single letters or initialisms. Words are easier to remember. They are easier to type on mobile devices with autocomplete. Typos are more obvious in common words. With words instead of single letters, typos are less likely to take you to an existing but incorrect page.

For almost a decade, the site used lightly customized Bootstrap 3: at first plain, then with the theme Sandstone from Bootswatch. Now the site uses its own stylesheet that partially imitates the look it had with Bootstrap. The site’s current palette is built around a tweaked subset of colors from Sandstone.

The site favicon is taken from the original Windows File Manager (winfile.exe). In 2018, Windows File Manager was released as free software under the MIT License.

The site implements dark mode using the prefers-color-scheme media query with a switch to override the OS/browser preference. It avoids the mistake of having a switch with only to states, light and dark, and allows the visitor to return to their OS/browser preference. The switch and the approach to dark mode are modeled on Gwern.net’s. The switch replaces the media attibute on a dedicated <style> element for dark-mode CSS.

Loading and storing the settings and replacing the media query is implemented in dark-mode.ts; the switch logic is implemented in dark-mode-switch.ts. dark-mode.ts stores the visitor’s preference in localStorage. While dark-mode-switch.ts is compiled from TypeScript and bundled with other JavaScript, dark-mode.ts is compiled and inlined in the page source, as is dark-mode CSS. This is done to prevent a flash of light on page load.

The site is built with a static site generator.

First, it bundles CSS, then compiles TypeScript to JavaScript with tsgo and bundles JavaScript. CSS and JavaScript are bundled by concatenation; they are not minified.

The generator then performs the following steps for each page:

The site is deployed using rsync over a multiplexed SSH connection.

Somewhat to my surprise, I have reduced the build-and-deploy time for the current version of the website to under three seconds. I’ve had to double-check changes to confirm they were actually deployed. This is the result of cumulative performance improvements: parallelism in the build step, switching from building a Debian package to rsync deployment, multiplexing SSH connections a different task, and most recently dprint.

The initial version of the site (later labeled 0.x) was a static HTML page with links to my profiles on other sites and a contact form. The links survive in the “elsewhere” section of the index page, and the contact form is largely unchanged. I wrote the pages in Markdown and converted them to HTML manually with John Gruber’s Markdown.pl. To store the page source code, I created a Git repository.

The manual process was soon replaced as I started developing the Tclssg static site generator. The focus of the site became its newly added blog, which lasted from 2014 to 2016. Blogging didn’t necessarily encourage me to write and publish. The blog is preserved. Tclssg remains in use outside my website. It has been adopted by some Tcl users and projects, including core.tcl-lang.org.

The second major version2020–2022 was a personal wiki served by Fossil SCM. After examining different wiki software and finding flaws in each, I went with one I was already using. I had noticed Fossil’s curious potential beyond source control. Fossil had enough wiki and theming features to serve a customized website. It let me edit the site’s contents in the browser. I joked that Fossil SCM was secretly “Fossil CMS”. This marked a temporary break from storing content in Git. I have keep the content and the code versioned separately since.

Packaging Fossil

For deployment, I started building a Debian package with the Fossil binary, Caddy configuration, and static files. When installed, the package replaced the previous version of the site as a whole; if installation failed, changes were automatically reverted.

A series of polemic comments by HN user Annatar describing his partices was what made me commit to this approach. Annatar later summaried the practices in a comment.It took some hacks to make Fossil do what I wanted. The wiki lacked categories and transclusion. At the time, it could not generate a table of contents for a page. I created a simple notation for tags and began generating a “tag page” using a Tcl script. The script ran when I synchronized my local Fossil repository with the server. (A Fossil synchronization is like a Git pull followed by a push.) The TOC was generated in JavaScript in the reader’s browser.

I enjoyed my time with a Fossil-based site. Being able to edit the wiki in the browser removed friction compared to a static site generator. However, I kept feeling Fossil’s limitations as a wiki engine. Beyond built-in categories and TOCs, I wanted the ability to version pages together. It’s easier to understand your site’s edit history when related changes to multiple pages are grouped together. Using the /doc/ page feature was an option but would have negated Fossil’s advantage of live wiki editing. I wrote fossil-wiki-export to have a migration path off Fossil and eventually used it.

I initially2022 wrote the third major version of the static site generator in Clojure. The site was still a wiki, only static. The code ran in Babashka and rendered a page template with Django-inspired Selmer.

Not long after2023, I ported the static site generator to Python to take advantage of the libraries and good optional static typing thanks to Pyright. The start with Selmer made it easy to translate the template to Jinja. Deployment still used a Debian package, now with only static files in it, until I migrated the site to BoxyBSD in 2025. With that migration, I switched to rsync deployment.

I was quite happy with the Clojure-to-Python port. By using ThreadPoolExecutor in Python and leaning on Pandoc Lua filters, I reduced the build time of the site to single-digit seconds. (I also wrote an experimental async/await version and discarded it after testing that it was slower than a thread pool.)

I consider shortcodes or macros essential for managing complex pages. They make a page easier to create and especially to maintain over time compared to raw HTML markup.

The macros in page Markdown went through several iterations. Tclssg allows you to write Tcl code in pages, which I used for transclusion and a more compact syntax for images. Those macros were gone with the switch to Fossil.

Macros in major version 3 of the site began as edn elements between <<< ... >>> delimiters. The first term determined the macro function to call, such as include, and the rest was passed as arguments. The string returned from the function replaced the delimited expression. These macros were only simple shortcodes without control flow. With the migration to Python, I replaced edn with shlex. The content required minimal changes because I didn’t use complex edn.

Most recently, I replaced custom macros with Jinja. This improved the macro system and, at the same time, reduced the line count in the SSG. What pushed me to do it was the need to optimize the size and image quality of the Chrontendo page, which had grown large with the addition of episode covers. A little testing of different image formats showed I both reduce the size and improve the quality with AVIF. However, I needed a fallback for browsers that didn’t support the still-new image format. Jinja let me define a macro in the body of the page that generated <picture> tags for AVIF images with JPEG fallback.

This is the macro:

<% macro cover(alt, src_prefix, attrs) %>

<picture>

<source srcset="<%= src_prefix =%>.avif" type="image/avif" />

<img alt="<%= alt =%>" src="<%= src_prefix =%>.jpg" <%= attrs =%> />

</picture>

<% endmacro -%>

The delimiters are <% ... %> and <%= ... =%> in place of Jinja’s standard {% ... %} and {{ ... }} to avoid conflicts with things like the Caddy templates.

I experimented with writing HTML in Python. After the Jinja template grew in complexity, I started thinking about how to make it more maintainable, and especially how to detect problems early. I looked into other template languages and was drawn to writing HTML in a Python DSL. This meant I could use standard tools like Ruff and Pyright to check the template.

I compiled a list of Python HTML DSLs and later picked htpy as the most mature. I kept Jinja for macros. The switch resulted in a mild performance improvement. Ruff’s linting and Pyright’s type checking were immediately useful with htpy. The Ruff Formatter was not. It didn’t format foo[bar, baz,] as multiline the way it would foo(bar, baz,). I quickly wrapped the layout in # fmt: off and # fmt: on to disable automatic formatting. To make the code more compact like HTML, I decided to indent with two spaces.

Formatting minified HTML

htpy only output minified HTML, and I wanted the final HTML to be readable and indented consistently. Consistent indentation was something I didn’t originally have with Pandoc output inserted in a Jinja template. Since whitespace matters in HTML, I looked for a formatter that wouldn’t break significant whitespace. My old go-to tidy-html5 had problems with it. The most proven option I found was Prettier. I was hesitant to add a Node.js dependency to the project for logistics reasons. It turned out to not be a hassle to manage. The formatting step only took a couple of seconds.

Later in 2025, there was a series of supply chain attacks on NPM. Prettier wasn’t affected. Nonetheless, I decided it was best to move away from NPM for something I didn’t watch closely. I found a suitable replacement in dprint. While Rust also has a culture of many small dependencies, it hasn’t seen a similar level of attacks. (Yet. Growth mindset.)In the end, I didn’t find htpy code particuarly easy to read or edit. I replaced htpy with a custom HTML DSL that was more readable to me and soon reverted to Jinja with regular HTML.

For comparison, here is a fragment of the page template in Jinja, htpy, and my custom DSL. Jinja first:

{% if show_metadata %}

<footer>

<div class="box metadata">

{% if "index" not in tags %}

<div class="metadata-dates">

Published {{ published }}, updated {{ updated }}.

</div> <!-- .metadata-dates -->

{% endif %}

<!-- ... -->

</div> <!-- .box .metadata -->

</footer>

{% endif %}htpy:

page.show_metadata and footer[

div(".box.metadata")[

page.tags and "index" not in page.tags

and div(".metadata-dates")[

f"Published {page.published}, updated {page.updated}."

],

# ...

]

]My custom DSL:

footer(

div(

f"Published {page.published}, updated {page.updated}.",

class_="metadata-dates",

if_=page.tags and "index" not in page.tags,

),

# ...

class_="box metadata",

if_=page.show_metadata,

),Unless indicated otherwise, all of my code on the pages of this site is distributed under the MIT License.

License pages like /mit-license/2026 are generated dynamically in an approach inspired by mit-license.org. This is documented on the Caddy page.

The site is built with open-source software. I am grateful to the authors and contributors of the following projects: Caddy, Combine (include_raw for Jinja), dprint, GoatCounter, highlight.js, highlightjs-copy, Jinja, Luacheck, net.lua, Pandoc, Poe the Poet, Python, rsync, Ruff, SingleFile CLI, StyLua, and uv.

Hosting is provided by BoxyBSD.